When a Buddhist hermitage in Sri Lanka is not enough

Daniel Hug (1975 –)

5 minute read

Read MoreUnhappy partners in an arranged marriage, Jacoub’s parents divorced when he was two, and he was raised by his father, who doted on him, sent him to the best schools in Baghdad, and encouraged his love of music and sports. On vacations in the picturesque mountains of northern Iraq, he stayed in first-class hotels with live bands and poolside dancing; and there were annual trips to an aunt in Lebanon whose summer home was situated in a village so pretty, it seemed “like paradise on earth.”

In 1976, Jacoub enrolled at the University of Baghdad to study chemical engineering. Four years later, in 1980, war broke out between Iraq and Iran.

A dreadful atmosphere settled over the country. Sirens blared in the cities whenever there was incoming Iranian aircraft. Everyone rushed to find a hiding place, or stood and watched, as Iraqi and Iranian fighter jets fought in the skies above us. It wasn’t long before “war martyrs” started to return: taxis, each with a flag-draped coffin strapped on top, flooded the streets.

In 1981 Jacoub was drafted. “No one wanted to join up, but we didn’t have a choice. Draft dodgers were executed.” After six months of basic training, he was transferred to a naval construction unit in Basra, where he was unexpectedly arrested by the Wasps, Iraq’s feared military police, because his beard was not regulation length. “I was locked up like a criminal. Later I learned that the sergeant of the police unit that arrested me had set a quota of fifty heads each day. I had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

At the military prison, Jacoub and fifty other men were forced into a broiling, stinking, closed shipping container. It was summer, the latrine was an open bucket, and sleeping meant dozing while leaning against another inmate, since there was no room to lie down. In prison, Jacoub met men who were serving terms of up to ten years. Luckily, he was able to negotiate a speedy release through a lieutenant who was an old acquaintance from engineering school.

After some eighteen months with the construction unit, Jacoub was transferred to combat training, and then sent off to a unit on the front.

It took army life to awaken me to the bitter truths of life in my country: blatant inequality, injustices of every kind, institutionalized slavery, and restricted freedom – especially freedom of expression. Our society in general seemed to be structured on hypocrisy and falsehood, but this was especially evident in the army. The gears of the whole machine were greased with bribes, favoritism, and behind-the-scenes manipulation.

During the war, the government gave substantial material inducements to the professional military staff: fat salaries and bigger mortgage loans, as well as other perks. For instance, the government ordinarily gave out a one-thousand-dinar “marriage grant” for couples getting married, but military personnel got three times that amount. Even more incredibly, professional staff could purchase a new car for one dinar. Depending on their rank, they could get anything from a Passat to a Mercedes. Those with means could buy their way out of the army. Old and disabled people ended up at the front, while people with political connections stayed in the rear lines or in the cities.

I began to ask, “What purpose is this war serving? Who is it benefiting?” As I saw it, it was the high government and military officials earning fortunes through greed and deception. The arms manufacturers raking in hundreds of millions. The politicians exploiting the war machine for their own personal advantage while holding forth on “freedom and democracy.”

Meanwhile, the coffins of the dead began to flood the cities and villages. Like some deadly combine, the war was harvesting thousands of souls from both sides of the battle lines. Many who were not killed lost limbs or had other serious injuries. Soon there were thousands of widows and orphans. Countless people lost houses, jobs, businesses, or farms and became refugees. Worse still, people lost their ethical principles. A deep depression swept over the nation.

I began to see that war is only a reflection of the human condition. When we stop listening to the voice of our conscience, when we close our hearts to our fellow humans, then war is inevitable, whether it is a family fight or the sort of major conflagration that tears countries apart.

At the front, Jacoub was soon questioning not only the war he was fighting, but war in general:

No one can truly know the horror of war until they have taken part in a battle: the deafening noise, eruptions on every side from falling artillery shells, screams, and the bloody, mangled bodies of people who were living comrades only moments before. Once, Hunnah, one of my relatives, was fleeing a dangerous situation with a friend during an offensive. As he ran, he looked over in horror: his friend, beheaded by shrapnel, continued to run for several more meters before collapsing. Hunnah blacked out. After he came to, he was so traumatized that he had to be hospitalized for a month.

I had entered a realm on the border of hell. Faces were pale with terror and exhaustion. Even the hardiest men were often reduced to cowering, whimpering children. I saw the specter of death wherever I turned.

The enemy was often a mere seventy-five meters away from us. Bombs, bullets, and shrapnel were continually flying in every direction. The dead and dying were on every side. I was tormented – not only by the horror of war, but also by the burden of my own guilt.

Around this time, Jacoub experienced a dramatic conversion that changed the course of his life: as he described it years later, a voice deep inside him cried out, “Enough!” He sought the priest of their local church and poured out everything that weighed on him in the darkness of a confessional. “I emerged light as a feather, and full of joy and hope. That was the most decisive moment of my life. It felt like a veil had been lifted, and I could see everything in a clearer light – the light of God.”

Suddenly, Jesus’ command to love one’s enemies and to return good for evil made perfect sense, as did his warning that those who “take the sword” will be killed by it:

Jesus refused to defend himself. So how could I defend myself with violence and still claim to be his follower? I could no longer hate others; I had to love them – to love all people. I had experienced the joy of forgiveness, a gift that gave me inner security and true peace.

I began to see that war is only a reflection of the human condition. When we stop listening to the voice of our conscience, when we open ourselves up to anger and hatred, when we close our hearts to our fellow humans, then war is inevitable, whether it is a family fight or the sort of major conflagration that tears entire countries apart. And if I can admit that I am part of the cause of every war, why can’t I also be part of the process of peace? I saw how forgiveness can break down barriers and pave the way for loving and harmonious relationships. I could be an instrument to help combat violence.

As he recounts in his memoir, I Put My Sword Away, Jacoub first considered simply going to the authorities and stating his position. But that seemed foolhardy: punishment for refusing to obey orders was death, and in any case, he knew of no church that would support him. Another route he contemplated was defection to the Iranian side, but that only tempted him until he considered its impact on his family. They would surely be interrogated and harassed. Another possibility, given his academic credentials, was volunteering to become a noncombatant professional. Or he could apply for a military-related job in the civil sector. “Of course, that also did not sit well with my conscience. After all, I would still be contributing to the violence just as much as if I were actually fighting.” One last option he considered was working for Iraqi intelligence.

Before long, though, I recognized that all these paths were nothing but compromises with the devil. And didn’t Jesus warn, “What will it profit you to gain the whole world, but forfeit your life?” So I felt I had no choice but to stay in the army and pray that the war would soon come to an end. I vowed to myself, however, that if I came face to face with the enemy, I would not kill, but rather let myself be killed. This decision cost me tears and intense prayers for God’s strength. But once I made it, I was determined to stick by it.

Read more of Jacoub's story in his memoir I Put My Sword Away.

5 minute read

Read More3 minute read

Read More2 minute read

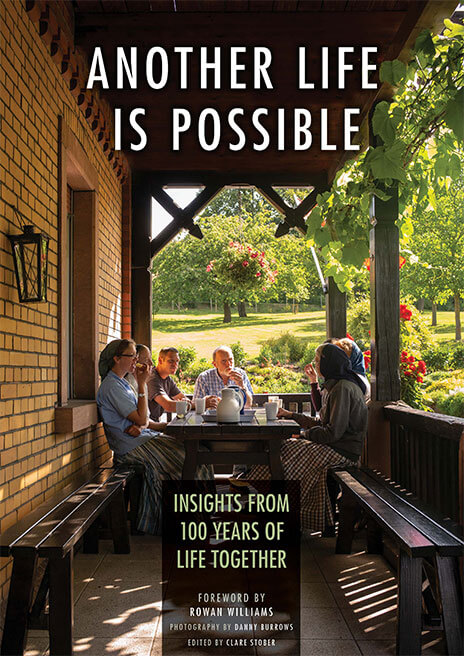

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.