A soldier in Saddam Hussein’s army who became convinced that he could no longer kill

Jacoub Sheghram (1958 –)

11 minute read

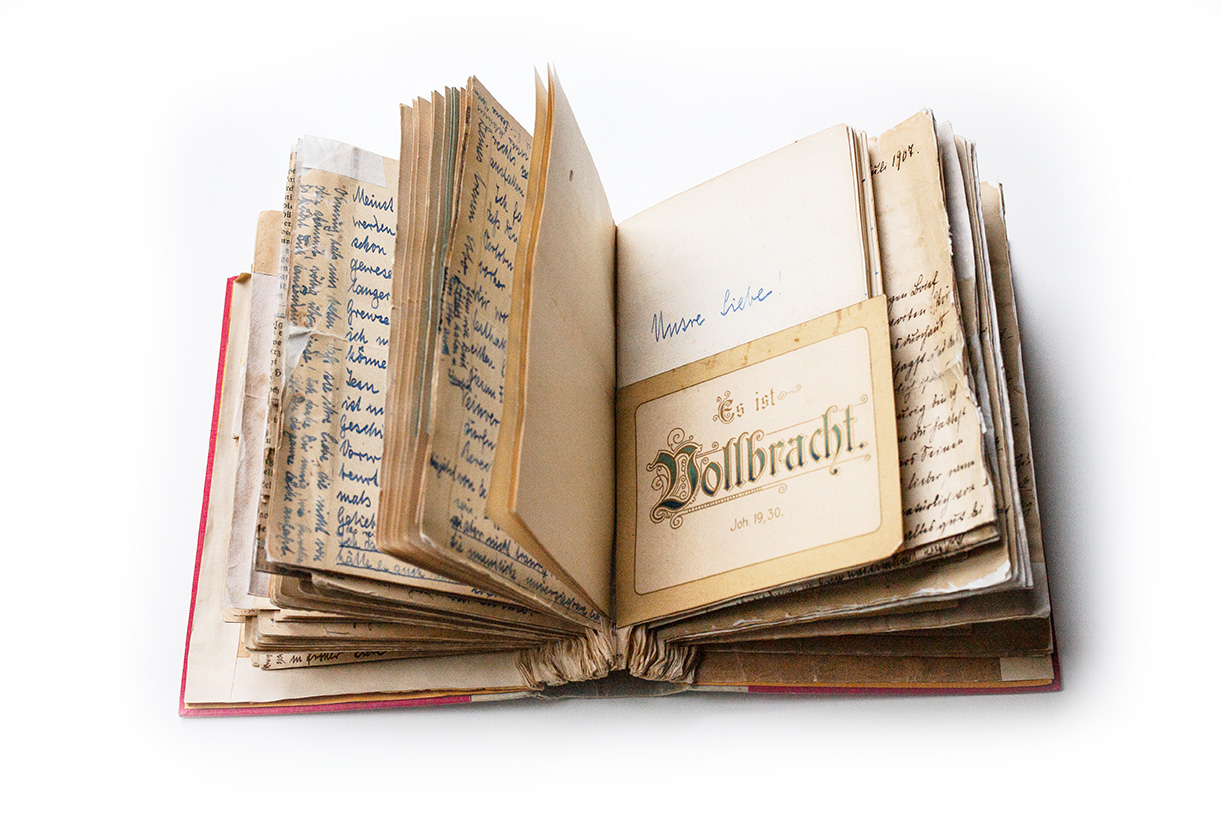

Read MoreBorn into a long line of German academics and himself a doctor of philosophy, Eberhard Arnold abandoned middle-class life to found the community now known as the Bruderhof. His own words describe his journey best:

In my youth, I tried to lead people to Jesus through the Bible, and through addresses and discussions. But there came a time when I recognized that this was no longer enough. I began to see the tremendous power of greed, of discord, of hatred, and of the sword: the hard boot of the oppressor upon the neck of the oppressed. . . . I had preached the gospel but felt I needed to do more: that the demands of Jesus were practical, and not limited to a concern for the soul. . . . I could not endure the life I was living any longer.

His spiritual awakening had begun years earlier when, as a teenager on summer vacation at the home of “Uncle” Ernst, his mother’s cousin, he had read the New Testament with fresh eyes. Ernst, a Lutheran pastor who had lost his church position after siding with the poor weavers of the region during a labor dispute, impressed him deeply. By the time he returned home, Eberhard was burdened with a new consciousness of his privileges and the plight of the impoverished.

The next years were tumultuous. He volunteered with the Salvation Army, started an intensive Bible study, and neglected his secondary school studies to such an extent that his desperate parents finally sent him to boarding school. When he graduated he clashed with them over the next step: Eberhard wanted to study medicine, while his father insisted on theology. Eberhard yielded.

This did not lead to the respectable career in the state church his father hoped for, however, as he was ultimately barred from sitting for his final exams. Through his study of the Bible and the influence of the evangelical revivalist movement, Eberhard came to believe that infant baptism was not valid and was re-baptized as an adult. This decision disqualified him from completing his degree. His parents disowned him, and the father of his fiancée, Emmy von Hollander, denied him permission to marry her until he had successfully defended another doctoral dissertation.

Eberhard switched his course of study to philosophy, completed a thesis on Nietzsche, and married Emmy in 1909. Meanwhile, he was making his voice heard as leader of the local chapter of the Student Christian Movement. The newlyweds moved from one city to another, following his work as a public speaker, while hosting gatherings in their home that attracted a lively and diverse attendance, from pious housewives to communist revolutionaries.

The First World War led the couple to read the Bible in a new light. Counseling wounded soldiers in an army hospital, Eberhard was shattered by what he heard and saw. Formerly an energetic advocate of the German cause, he embraced pacifism as truer to the gospel.

The end of the war in 1918 heralded little in the way of peace: there were strikes, assassinations, revolutions, and counterrevolutions, and finally the haphazard birth of the Weimar Republic. In Eberhard’s words, the hour demanded a discipleship that “transcended merely edifying experiences.” Increasingly he pondered the evils of mammon, the god of money and material wealth. “Most Christians have completely failed in the social sphere and have not acted as brothers to their fellow man. They have risen up as defenders of money and capitalism,” he said. An alternative emerged, simple but all-consuming:

Jesus says, “Do not gather riches for yourself.” That is why the members of the first church in Jerusalem distributed all they had. Love impelled them to lay everything at the apostles’ feet; and the apostles distributed these goods to the poor.

Christ’s love calls us to give up our possessions, too. That is the only way to help the world; it strikes at the root of our selfishness, making it possible for us to live in harmony – to live a life of love and justice and community.

As Emmy wrote in an unpublished memoir:

Social contradictions such as the fact that one person can enjoy the plenty of life without sweating, while another does not have bread for his children despite working like a slave, occupied us more and more. Through reading the Bible, we realized that this is not God’s will.

From the outset of our friendship, Eberhard and I had wanted to give our lives in service to others. That was our primary concern. So it was perhaps natural that we now found ourselves joining with people who were dissatisfied and were challenging public life and human relationships with the old slogans of freedom, equality, and fraternity. These ideals were drawing people from all walks of life; and all of them were struggling to find God’s will, even if few would have expressed it like that. . . .

Christ’s love calls us to give up our possessions, too. That is the only way to help the world; it strikes at the root of our selfishness, making it possible for us to live in harmony – to live a life of love and justice and community.

At a series of open evenings in our house we read the Sermon on the Mount and were so overwhelmed by it that we decided to completely rearrange our lives according to it, cost what it may. Everything written there seemed to have been spoken directly to us: what Jesus says about justice, about hungering for righteousness, loving one’s enemies, and finally, about actually doing God’s will.

But Eberhard’s radical pacifist and economic views were incompatible with his employer, Die Furche, the publishing house of the Student Christian Movement where he had worked since 1915. In early 1920, Eberhard gave notice and, in June of the same year, the Arnolds took the plunge. Surrendering their life insurance policy for cash and leaving their comfortable Berlin home, they moved with their five children to Sannerz, a poor farming village, where they began living in full community with several other like-minded seekers, including Emmy’s sister Else.

Starting such a community, as Emmy wrote later, required a leap of faith:

We had no real financial basis of any kind for realizing our dreams. Not that it made a difference. It was time to turn our backs on the past, and start afresh – to burn all our bridges, and put our trust entirely in God, like the birds of the air and the flowers of the field. This trust was to be our foundation – the surest foundation, we felt, on which to build.

The Arnolds were hardly alone in their thinking: their fledgling community was one of dozens of similar settlements that had sprung up across Germany at the time, attracting young people disillusioned with both bourgeois piety and social inequality. More than a thousand guests descended on the community in Sannerz during its first year.

From his new home base, Eberhard soon resumed publishing with the mission, as he wrote, of “allowing the gospel to work in creation, producing literary and artistic work in which the witness of the gospel retains the highest place while at the same time representing all that is true, worthy, pure, beautiful and noble.” He saw Sannerz and other exemplars of voluntary Christian community as beacons of hope – models that could inspire other attempts at social and economic renewal. This would surely happen, he believed, once people’s eyes were opened to the possibilities of brotherhood and the joy of sharing everything in common, as opposed to competing for every last coin. As he said at a lecture in 1929:

People tear themselves away from home, parents, and career for the sake of marriage; they risk their lives for the sake of wife and child. In the same vein, people must be found who are ready to sacrifice everything for the sake of this way, for the service of all people.

Community is alive wherever these small bands of people meet, ready to work for the one great goal, to belong to the one true future. Already now we can live in the power of this future; already now we can shape our lives in accordance with God and his kingdom. This kingdom of love, free of mammon, is drawing near. Change your thinking radically so that you will be ready for the coming order!

By this time the community had grown, its ranks expanded by homeless war veterans and single mothers, orphans and day laborers, people with disabilities and mental illness, anarchists and communists, Christians and Jews. To accommodate this new influx, it resettled on a farm in the Rhön hills.

Meanwhile, Eberhard had become increasingly interested in the example of the Anabaptists, who emphasized unity, sharing of possessions, nonviolence, and the church as a “city on a hill.” He learned that one branch of this movement, started by Jakob Hutter in the sixteenth century, had existing communities in North America, and he reached out to establish a relationship with them.

The rise of National Socialism in the 1930s presented Eberhard and the other members of the Bruderhof with the challenge of remaining faithful in an increasingly hostile state. The pacifism of the early Anabaptist movement remained a core principle of their identity, despite the persecution they knew it would bring. This also meant that, from the very beginning, they distanced themselves from the regime. The Bruderhof’s connections to Jewish communities also strengthened their resolve against the anti-Semitic aims of the Third Reich.

The first of several Gestapo raids occurred in 1933. Eberhard was not intimidated, and sent off reams of documents to the local Nazi officials, explaining his vision of a Germany under God. He even wrote to Hitler, urging him to renounce the ideals of National Socialism and to work instead for God’s kingdom – and sending him a copy of his book Innerland, which spoke forcefully against the demonic spirits that animated German society at the time. Not surprisingly, this letter was never answered.

Following the raid, Bruderhof parents quietly began the process of evacuating the community’s children to Liechtenstein. When a Nazi-sanctioned teacher showed up to take over the school in 1934, she found no pupils waiting for her. With hostilities in Germany rising, the whole community soon moved to Liechtenstein, but did not stay for long – from there they left for England, and later Paraguay.

Eberhard did not live to shepherd them through these changes, however. His death came suddenly in 1935, the result of complications following the amputation of a poorly set broken leg. Under extremely difficult circumstances, others took up the work he had begun.

Remembered a century later, his “voice of one crying in the wilderness” delivers “a wakeup call for the religiously sedated and socially domesticated Christendom of the Western world,” writes Jürgen Moltmann, a German theologian. “He saw down to the root of things, leading to uncompromising decisions in the discipleship of Jesus between the old, transient world and the future of God’s new world.”

“It may seem strange that such an insignificant group could experience such lofty feelings of peace and community, but it was so,” Eberhard wrote shortly before his death. “It was a gift from God. And only one antipathy was bound up in our love – a rejection of the systems of civilization; a hatred of the falsities of social stratification; an antagonism to the spirit of impurity; an opposition to the moral coercion of the clergy. The fight that we took up was a fight against these alien spirits. It was a fight for the spirit of God and Jesus Christ.”

Explore an archive of Eberhard Arnold's writings at EberhardArnold.com

11 minute read

Read More17 minute read

Read More3 minute read

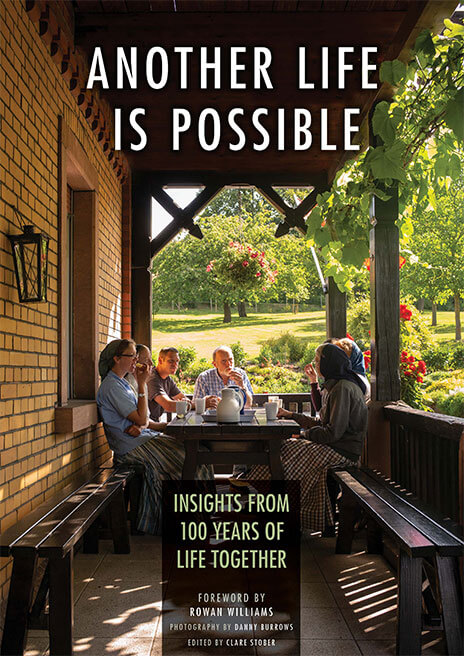

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.